Directed by Jacques Tati. 1958.

Mr and Mrs Arpel have really everything they want, they have achieved every success, everything is new in their house: the garden is new, the house is new, the books are new. And I think they need to be warned, somebody should definitely say to Mr Arpel: “Be careful, you should not forget a bit of humour! Your son is only nine and I think you should enjoy yourself and have a good time with him.” People think it is a message but it isn’t: one should be free to say to a man who is building a house “Be careful. It might be too well-built.”

- Jacques Tati

Creating and maintaining that personal tone is perhaps Tati’s greatest achievement in

Mon Oncle. Like

Playtime,

Mon Oncle is not a hyper-intellectualized criticism of modernity. Nor is it an unsparing critique of consumerist habits. Rather it is a wistful look back at the world Tati knew and loved, and a quizzical, apprehensive look at the one he saw replacing it. He sets up the contrast no sooner than the opening credits, where the camera pans down the names which are neatly typed out on a neatly designed sign at the loud construction site of a new building. In contrast, the title card is a plain old street corner from Mr. Hulot’s town, with

Mon Oncle scrawled on the wall in chalk. Dogs walk by and relieve themselves on the street lamp.

That image, however inglorious, is not a bad representation of Hulot's world. It has puddles, garbage, misshapen patches of grass, cracked stones, and yes, dogs do relieve themselves. It is a lived-in world and one that reflects what the people who live there do. Tati’s town was not built at once according to one master plan, but built and changed over many years as people came and went, as families grew and people passed on. Like his house, it many ad hoc solutions, little cribs, additions, and cheats to meet a new need without destroying what was there.

Sure, it is a rigmarole to get in, but what character it has! Mismatched shutters, mixed styles, hanging laundry, and so on. One wonders many people, how many generations worked on it. It reflects the characters of those who do, and who have, lived there. It is also, of course, Hulot’s home, filled with his friends and neighbors, so why would he want to live elsewhere?

Now the Arpel’s house is certainly a contrast to Mr. Hulot’s, but not so much in terms of outcome as of intent. Sure Hulot’s apartment building is inefficient, but it was not designed with the pretension of efficiency. The Arpel’s house is designed to be the pinnacle of modern style and efficient design. The house was built according to a plan, but a thoughtless, inhuman one. The building is simply not conducive for living. Take the kitchen for example, which looks like a cross between a dentist’s office and a NASA laboratory. It has every convenience, but it is cold and unwelcoming. The appliances buzz and whirr and crank. Even something as simple as a cabinet, which might have a gentle squeak as cabinets often do, instead has been engineered into a mechanical maw which nearly has Hulot’s hand for supper.

The yard is also quite a spectacle. It is large and walled off for privacy. It is the home of a ghastly fountain that only gets turned on for visitors and this touch most epitomizes the whole situation of the Arpels: they have all of this stuff that is not really

for them. They have the fountain because it is supposed to impress others or display affluence. They have all of these conveniences and time-saving appliances, and what do they do with the time they save? They spend it on more time saving devices or they spend it away from their house. Have they really thought about what they would like to do, for its own sake? Of course none of what they do is bad, really, but it looks so silly because it is not done for any particular end. Look at the yard:

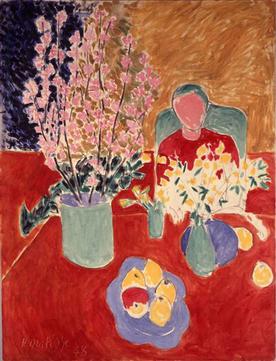

It is designed into many sections and cordoned off so you are only “supposed” to walk in certain areas. Why? Look at the picture above. In the scene, the party had to move from the other side of the yard to this side to sit down and eat, but there is no room because there is no other space sectioned off “for eating.” They have this big yard and cannot use it for what they want. In the scene depicted above, which may have presaged a similar scene in Playtime that uses cars instead of people, the characters walk around that little square like a circus line, amplifying the ridiculousness of the situation. We are glad to see later, when a dog gets loose at the party, the people running around trying to catch him. We want to say, “Yes, good! Go, run over the lines! It’s your yard, you can set the rules. Have fun in it and make a bit of a mess for once!”

Hulot’s brother in law works is a similarly sterile and highly polished, impersonal world. Trying to make Hulot more like himself, Mr. Arpel asks his boss to hire Hulot. The boss’ office looks like the lair of a James Bond villain, with ceilings so high they are out of sight, strange silver chairs, a map of the world in the back, and the boss sitting at an enormous desk. While in the office, Mr. Arpel phones Hulot to offer him the job, but wherever Hulot is, music is playing and Arpel cannot hear him. In a brilliant touch, Tati lets the music take over the soundtrack, and delightfully, it is as if Mr. Hulot’s world is pouring into that big and cold room, warming it and giving it life for the first time. Of course the company is not up to any nefarious business like world domination and that is the point, why does it look like that? Why should someone's office, where someone works, be so uninviting? Even Arpel’s briefcase, which looked chichi at home when his wife neurotically dusted it, looks warm in such a hostile atmosphere.

Indeed it is atmosphere, specifically a personable one, that lies at the heart of Hulot’s world. The Arpel’s house, for all of its order, is in fact an order imposed upon them and not by them, and their house reflects their desire to live apart from others. (Recall that cursed, clanking, buzzer-operated fence that closes off their yard.) The human relationships are the heart of Hulot’s town, for better and worse. It is human incongruities that made it mismatched and imperfect, but also the desire of its people to live there, together, that kept it together. The combination of those two elements made it unique. The film’s title suggests what Tati’s quote about the film does: the desire to remind people who choose to live the “new way” to make the human component the heart of their endeavor. Hulot’s nephew is dreadfully unhappy at home. Quite simply, it is too clean and boring and more like living in a hospital ward than a home. When he goes out with his uncle, he rides on his bike amongst the townspeople (as opposed to riding past them in a car,) he eats jam-covered crullers with extra sugar, and plays pranks on people with other boys in the town. The boy’s classic prank, and a running gag throughout the film, is to whistle at someone as he approaches a pole in order to get him to turn around and look at you and thus crash into the pole. Towards the end of the movie, the boy’s father accidentally pulls the prank on someone and the boy grabs and squeezes his father’s hand in excitement as they try to sneak away. It is a beautiful little moment and we hope his father can learn from it.

We hope he learns what Mr. Hulot has taught us, that you have to be willing to make yourself a little vulnerable and go out and live with your neighbors. Sometimes you get splashed, covered in dust, or punched in the face, but that is probably better than having nothing happen at all, the same way the folksy little “town tune” is preferable to the silence of the Arpel household. Yet there is a certain wistful sadness to Mon Oncle, for just as surely as Mr. Hulot was moving away, the old world was passing. This theme is conveyed throughout the movie by cutting to a scene of construction workers tearing down an old building with pickaxes. The town is such a character this feels a surprisingly violent act, but we should not be too alarmed. It is not really the stuff we should be concerned about. Some change is normal, like Hulot’s little neighbor who is all grown up when he leaves. We should just make sure we do not get carried away with change just because it is novel and that we never forget the human element, the

humour as Tati said; and in

Mon Oncle Tati is not scolding or imploring us. The tone of Mon Oncle is not that of a self-righteous spokesperson crusading for a better world or an intellectual browbeating you into accepting his aesthetic philosophy. It’s more like your neighbor leaning over your fence as you remodel your home and saying to you, “You’re going to add what? Really? Oh. . . Really?”